Individual beliefs and why they matter

1.1.2.1

An experiment in revealing individuality

1.1.2.2 Spotting your differences

1.1.2.3 Same word, different constructs

1.1.2.4 Every teacher is different

1.1.2.5 Beliefs, assumptions, knowledge: a note on terminology

1.1.2.6 Beliefs and action

1.1.2.7

Beliefs and teacher development

1.1.2.8 Introspection and reflection

1.1.2.9 Beliefs as pedagogical baggage

1.1.2.10 A warning!

1.1.2.1

An experiment in revealing individuality

Here's an experiment for you to try with some friends, colleagues or students,

or you can do it on your own. It might not seem very relevant to the topic

of this module at first sight, but bear with it, and all will be revealed!

When you click the link below, you will see a word (DON'T LOOK YET!).

As soon as you've seen it, spend a minute or so focussing on what it means to you. Think of all the sights, sounds, smells, tastes, textures and emotions that word evokes for you. If you like, jot these down, or draw a mind-map.

After a minute or two, compare notes with your friends (or look at the examples provided).

Now click here to see the word.

1.1.2.2

Spotting your differences

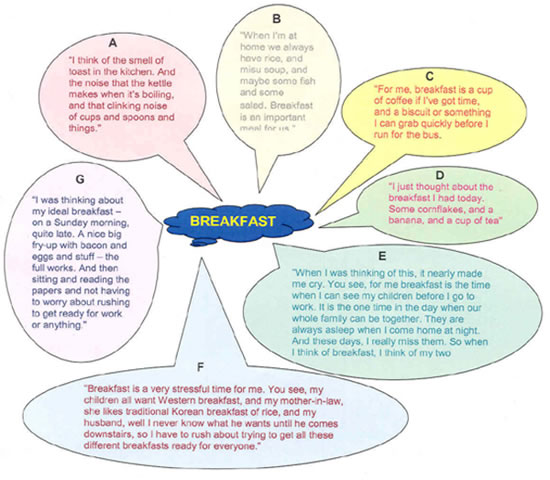

In case you are working alone, here are some summaries of responses to

this exercise that workshop participants have made:

How did your response compare with these, or those of your work partners?

1.1.2.3

Same word, different constructs

What always strikes me when I do this exercise with a group is the great

variety of responses offered. No one (yet) has ever come up with anything

like a dictionary definition for 'breakfast'. Instead, some describe what

they eat for their typical breakfast, like A, B and C. But A and B have

strikingly different meals, reflecting the customs of their different

countries (UK and Japan).

Some, like A, have quite a detailed image, including smells and sounds; others, like B, comment on the status of the meal, in contrast to those who, like C, simply list what they eat, but relate this to some other part of their routine, like running for the bus. D describes a specific breakfast, the one she had today, while G dreams of his ideal breakfast. E and F both have quite strong emotional reactions. In fact E, who comes from Japan, doesn't talk about food at all, but about his family (when he made this comment, he was away from them for a year while he did his MA in England). And F, a British woman married to a Korean and living in South Korea with her mother-in-law (and who actually went on to say a lot more than I've included here!) sees breakfast as epitomizing her split role as British mother, Korean daughter-in-law and wife! I got the impression that she never actually got round to having any breakfast herself!

So an apparently simple, single concept can evoke a whole range of images in different people, including not only things to do with physical environment or sensations, but also roles and relationships with other people, and emotional reaction to these.

1.1.2.4

Every teacher is different

Now imagine doing the same exercise with the word TEACHER.

Or student

Or classroom

Or language

Or language learning

Or …

Well, I think you get the idea!

When you describe yourself as a 'teacher' you almost certainly have a different image in your own mind of what this means, in terms of your roles, responsibilities and practices than each of your colleagues and students. The fact that we each have very personal belief systems, or mental constructs, concerning our professional personae and related areas has some important implications.

1.1.2.5

Beliefs, assumptions, knowledge: a note on terminology

The term belief generally refers 'to acceptance of a proposition

for which there is no conventional knowledge, one that is not demonstrable,

and for which there is accepted disagreement' (Woods 1996:195)

Knowledge refers to 'things we "know"- conventionally accepted facts, (which) […] in our society today […] generally means (something) that […] has been demonstrated or is demonstrable' (ibid:195).

An assumption, in contrast, is the temporary acceptance of a fact which we cannot say we know, and which has not been demonstrated, but which we are taking as true for the time being (ibid:195).

According to writers such as Woods, knowledge, assumptions and beliefs are part of a single system, where the more belief characteristics that are present, the more we can think of a structure as being a belief rather than knowledge. That is, beliefs, assumptions and knowledge are seen not as distinct concepts 'but as points on a spectrum of meaning' (ibid:195).

These background knowledge and belief structures (also referred to as 'schemata', 'scripts', 'conceptions', 'preconceptions', and 'images'; see Woods, 1996: 59 and 192-93) are the mental constructs with which our minds represent, and make sense of, the world.

This is what I mean in this module when I refer to 'beliefs'.

1.1.2.6

Beliefs and action

Williams and Burden (1997: 56)

report 'a growing body of evidence to indicate that teachers are highly

influenced by their beliefs, which in turn are closely linked to their

values, to their views of the world and to their conceptions of their

place within it.'

Pajares (1992) goes so far as to claim that teachers' beliefs are more influential than their knowledge in determining teaching behaviour. Williams and Burden (1997: 56-57) reiterate this: 'Teachers' beliefs about what learning is will affect everything that they do in the classroom […] deep-rooted beliefs about how languages are learned will pervade their classroom actions more than a particular methodology […] or coursebook' (my emphases).

So background knowledge and belief structures play a fundamental role in the way teachers act.

1.1.2.7

Beliefs and teacher development

Belief / knowledge

structures are also crucial in determining how people interpret events.

Every new experience (including formal learning experience) is interpreted

through the filter of existing knowledge structures, which in turn may

be modified to incorporate the new information.

When someone experiences something new that challenges the way they think the world is, they may ignore the new information that seems not to fit, or decide that they actually heard or saw something else ('That can't be right! It must have been like this …'). Alternatively, they may try to stretch or even completely reconstruct their understanding to find a way to accommodate the new experience.

With respect to teacher development, teachers' conceptions of their subject and teaching may provide either a positive or a negative filter for any new knowledge they encounter.

1.1.2.8

Introspection and reflection

The way that you are reacting now to the ideas and activities in this

module will be unique, and will depend on how familiar the ideas are,

and how close they are to your existing beliefs and knowledge.

I recommend that before you continue, you take five minutes to think about what you've read so far.

If you are working on this material with colleagues, compare your reflections with them, and explore any differences in your reactions. Can you explain why your reactions are different?

1.1.2.9

Beliefs as pedagogical baggage

Teachers' views about language teaching and classroom events are influenced

by 'the ways in which they have interpreted what they have learned as

they became teachers' (Woods, 1996: 58).

I would also include what they have learned in the thousands of hours

spent in the classroom as a student (cf Lortie,

1975).

Even 'beginner' language teachers come to teaching with a sophisticated idea of what it means to be a teacher, and what it means to learn an additional language. I know that during my first sessions in the classroom as a teacher, I clung to the image of a tutor I had at college whom I greatly admired - my image of a 'good teacher' - and tried to emulate her. A Spanish colleague told me of a contrasting experience: she avoided teaching in the way she was taught English, because the experience had been so negative. We all come to teaching with our own unique pedagogical baggage, some useful, some not.

The danger is that unless we unpack this baggage, we may unconsciously adopt practices that are not useful, and that we would choose to avoid if we had thought about them.

Equally, we may become more aware of positive influences that we would like to inform our classroom practice more than they already do.

1.1.2.10

A warning!

In the past many supposed facts about how learning takes place, and how

a teacher can best facilitate it, have been challenged (a well known example

in our field is Chomsky's criticism of Skinner's behaviourist theories

of language learning; a good report of this is given in Chapter 1 of Aitchison,

1989). In reality, many of these 'facts', especially those concerning

how best to teach, were little more than beliefs or unsubstantiated assumptions,

and although researchers and theoreticians are working to increase our

knowledge about second language learning (and teacher development) processes,

we should remain cautious of what we think we know about

how best to teach, or how learning happens. Paradoxically, this caveat

must also apply to the ideas and pedagogic recommendations put forward

in this module!